The Ebionites, a Jewish Christian sect that thrived in the first and second centuries CE, have left a limited textual footprint. This sect, known for strict adherence to Jewish law and the rejection of Paul’s teachings, made a significant impact in the early centuries of Christianity.

Insights from early Church fathers such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Origen, and Epiphanius provide crucial information about this mysterious group. These sources offer valuable insights into their beliefs and practices, but they also reflect the biases and perspectives of their authors.

The Ebionites were primarily located in Judea and Galilee, with additional communities in Syria, Egypt, and Asia Minor. Despite declining popularity after the fourth century, they persisted within synagogues until the 8th century, eventually assimilating back into Judaism. Their influence, however, endured within early Christianity, and includes remnants of Ebionite traditions persisting in present-day Ethiopia.

Lets explore the mysterious world of the Ebionites, an fascinating and enigmatic sect that significantly influenced early Jewish Christianity, left a lasting impact despite their limited textual footprint. Through unraveling their beliefs, practices, and historical backdrop, we can grasp a profound comprehension of their lasting legacy and their pivotal role in shaping the religious milieu surrounding the historical Jesus, unraveling details about his family and followers beliefs prior to the advent of Catholic Orthodoxy.

The Ebionites recognized Jesus as a Prophet, anointed by God, at his immersion but denied his divinity, who called for an end to temple sacrifices, due to this they eschewed the consumption of meat much like some of the Essenes, viewing Jesus as merely a human born to Joseph and Mary. Committed to the Jewish law, they practiced conversion to Judaism, circumcision, adhered to dietary restrictions, and observed the Sabbath.

The Ebionites preserved elements of Jewish Christianity within their communities, this offers a different perspective on the relationship between Rabbinic Judaism and early Jewish Christianity, than the later developed Catholic Orthodoxy that diverged greatly from this foundation.

Rejecting Paul’s teachings as divergent from the Jewish law, the Ebionites, played a foundational role in early Christianity. While they faded over time, their influence persisted in groups like the Mandaeans and Nazarenes, who eventually contributed to the development of Pauline Christianity and the establishment of Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

By the conclusion of the second century, Christianity, influenced significantly by Marcion’s emphasis on the Pauline letters, which he “found,” explicitly distanced itself from Judaism and Jewish culture. A shift occurred whereby the majority of Christians had forsaken adherence to the Law.

In the second century, non-Jewish followers of Jesus began identifying themselves as a distinct “third race,” aiming to differentiate from both Jews and idol worshippers. Divergent theological interpretations regarding the destruction of the Temple emerged, with Rabbinic Judaism viewing it as a consequence of neglecting the Torah.

Scholars suggest that the emergence of Adversus Iudaeos rhetoric was driven by the theological threat posed by Fiscus Iudaicus, a tax on practicing Judaism that led many to abandon it due to the heavy cost. By the second and third centuries, Jewish ethnic identity markers and rituals faced dismissal and demonization within the Christian context.

Their name, “Ebionites,” stemming from the Hebrew “evyon” meaning “poor,” encapsulates their commitment to simplicity and adherence to Jewish customs. This may have been a self-designation, or it may have been a derogatory term used by their opponents.

James the brother of Jesus assuming leadership in the Jerusalem synagogue is widely accepted as a historical fact. Michael Goulder, in “St. Paul versus St. Peter,” dismisses the notion that ‘Ebionite’ Christology originated in the late second century.

Instead, he asserts that this Christology, documented by Irenaeus around 170, was the creed of the Jerusalem congregation since its early days. The assertion of James heading the Jerusalem community is well-established, as highlighted in an ABC interview with Pierre-Antoine Bernheim.

Originating in the first century CE, the Ebionites constituted the original Jewish-Christian sect. Noteworthy for their strict observance of Jewish customs, the sect also stood out for rejecting the divinity of Jesus, denying the virgin birth, they didn’t believe in the resurrection either and exclusively relying on their own Hebrew Gospel while rejecting the writings of Paul and his teachings as heresy.

“Those who are called Ebionites accept that God made the world. However, their opinions with respect to the Lord are quite similar to those of Cerinthus and Carpocrates. They use Matthew’s gospel only, and repudiate the Apostle Paul, maintaining that he was an apostate from the Law.” – Irenaeus, Haer 1.26.2

According to the Ebionites, as described by Epiphanius of Salamis in Panarion 30.16.6–9, they assert that Paul was originally a Greek. Allegedly, he journeyed to Jerusalem, where he developed a desire to marry the daughter of a priest. In pursuit of this union, he converted to Judaism and underwent circumcision.

However, when his proposal was rejected, he became enraged and subsequently wrote against circumcision, the Sabbath, and the Law, this is also reflected the story of Simon Magus in Toledot Yeshu, considered by many to be Paul or one of his associates, as well as the writing of Celcus.

According to Robert Eisenman’s analysis, James, emerges as the paramount leader of the early movement. During James’ influential period in Jerusalem from the 40s to the 60s CE, other centers held little importance. The term “Bishop of the Jerusalem” Congregation or “Leader of the Jerusalem Community” becomes less significant during this time.

John Painter, in “Just James – The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition,” suggests a probable connection between early Jerusalem Jewish Christianity (the Hebrews) and the Ebionites. Author James Tabor suggests that the Ebionites and the early followers of Jesus, are one and the same, that they offer our best witness to what the early Jesus community was actually like.

Although the historical influence of the Ebionites waned over time, their unique perspectives and practices offer valuable insights into the complex landscape of early Jewish Christianity. The origins of the Ebionites remain unclear, with the earliest references coming from the writings of Justin Martyr (c. 100-165) and Irenaeus (c. 130-200).

The earliest reference to the Ebionites appears in Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho around 140 CE, provides one of the earliest mentions of a sect resembling the later Ebionites. Justin Martyr describes the Ebionites as “those who follow the teaching of the twelve apostles” and who “accept only Matthew’s Gospel, and use it with the Hebrew translation.” He also says that the Ebionites “reject the apostle Paul, and call him an apostate from the law.”

It was Irenaeus, on the other hand, circa 170 CE, was the first to use the term “Ebionites” to name a specific sect of Jewish Christians, calling them “heretics” and “Judaizers.” He accuses them of rejecting the virgin birth of Jesus, denying his divinity, and following the Jewish law too strictly.

Gerd Ludemann, in “Heretics: The Other Side of Early Christianity,” addresses the historical connection between the Ebionites and the Jerusalem community. Despite a century gap between the Jerusalem community’s end and Irenaeus’ report, Ludemann presents reasons supporting the plausibility of Ebionites as an offshoot of the Jerusalem community.

He emphasizes that the term “Ebionites” might be self-designated, and the hostility to Paul and adherence to the law, particularly circumcision, align with groups originating from Jerusalem before 70. Ludemann suggests that Justin’s Jewish Christians act as a historical link between pre-70 Jewish Christianity in Jerusalem and the later Jewish Christian communities mentioned by Irenaeus.

In the exploration of second-century Christian “heretics,” Antti Marjanen and Petri Luomanen make a noteworthy observation in their work “A Companion to Second-Century Christian ‘Heretics’.” They highlight the intriguing emergence of the Ebionites in catalogues during the latter part of the second century. The initial reference to the Ebionites finds a place in a catalogue utilized by Irenaeus in his Refutation and Subversion.

Symmachus, mentioned by Eusebius in Historia Ecclesiae VI, xvii, is identified as an Ebionite. According to Eusebius, the Ebionite heresy maintains that Christ is the son of Joseph and Mary, viewing him merely as a human and insisting on strict adherence to Jewish law.

Symmachus’ surviving commentaries, according to Origen, reflect his support for this heresy by criticizing the Gospel of Matthew. Origen obtained these commentaries from Juliana, who inherited them from Symmachus himself. Jerome, in De Viris Illustribus, chapter 54, and Church History VI, 17, also make reference to Symmachus.

Oscar Skarsaune, in “Jewish Believers in Jesus,” challenges Eusebius’s assertion that Symmachus was an Ebionite. Skarsaune suggests that Eusebius may have inferred Symmachus’s Ebionite affiliation based on his commentaries on specific passages in the Hebrew Scriptures. For instance, Symmachus’s interpretation of Isaiah 7:14, using “young woman” instead of the LXX’s “virgin,” is seen by Eusebius as an attack on the Greek Gospel, as it follows more accurately the original Hebrew of the Tanakh.

The Ebionites are also mentioned by other early Christian writers such as Origen (c. 185-254), Eusebius (c. 260-339), and Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 315-403), offering additional insights into their beliefs and practices. These sources reveal that the Ebionites exclusively used the Gospel of Matthew, considering it the sole authentic gospel. Their belief in Jesus as a Prophet coexisted with a denial of his divinity. The Ebionites rigorously adhered to the Jewish law, encompassing practices like circumcision and the Sabbath.

Origen, in approximately 212 CE, notes that the name finds its roots in the Hebrew word “evyon,” signifying ‘poor,’ noting that they “believe that Jesus was born of a virgin, but that he was not of divine nature.” Further, similarly he mentions their strict adherence to the Jewish law, encompassing practices like circumcision and Sabbath observance.

Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403) offers a comprehensive account of the Ebionites in his heresiology, Panarion, where he condemns eighty heretical sects, including the Ebionites. According to Epiphanius, the Ebionites exclusively embrace Matthew’s Gospel, utilizing it in conjunction with the Hebrew translation. Furthermore, Epiphanius underscores their commitment to the Jewish law, emphasizing practices such as circumcision and Sabbath observance.

“Perhaps the oldest are those named after the groups which employed them: those according to the ‘Hebrews’, the ‘Egyptians’, and the ‘Ebionites’. Hebrews seems to consist essentially of a modification of the Gospel of Matthew in the direction of Jewish Christianity; its hero is James the Lord’s brother, recipient of a special resurrection-appearance (cf. I Cor. 15.17), and head of the Jerusalem church.” – Robert M. Grant, A Historical Introduction to the New Testament

The term “Ebionites,” or more accurately “Ebionæans” (Ebionaioi), has its roots in an Aramaic expression signifying “poor men.” Eisenman argues that “the Poor” served as the designation for James’ Community in Jerusalem, and this community or its descendants, particularly the Ebionites, endured in the East for the subsequent two to three centuries.

The precise meaning of the term remains elusive, with Origen and Eusebius suggesting that the label was given to this sect due to their strict adherence to the impoverished Law, interpreting “poor” as a derogatory term for the Torah rooted in replacement theology.

Robert Eisenman, in “The New Testament Code,” underscores the association between the ‘Ebionites’ and the followers of James, who is regarded as the preeminent leader of ‘the Poor’ or the same ‘Ebionites.’ Notably, James, even in early Christian accounts, holds a prominent position among ‘the Poor.’

Eisenman draws attention to James 2:5, emphasizing that it is the ‘Poor of this world’ (‘the Ebionim’ or ‘Ebionites’) chosen by God as heirs to the promised Kingdom for those who love Him. The term ‘the Poor’ or ‘Ebionim’ is intricately linked to James and his community, identified as ‘the Ebionites’ or ‘the Poor’ in early Church literature.

Certain scholars posit that the concept of the Ebionites can be discerned in Paul’s references to a collection for the “poor” in Jerusalem (Gal. 1:10). However, in Rom. 15:26, Paul draws a distinction between this sect and other Jerusalem believers, specifically mentioning “the poor among the saints.”

In 2 Cor. 9:12, Paul reinforces the economic or literal dimension, characterizing the collection as a means to address “the deficiencies of the saints.” E. Stanley Jones explores this perspective in the article “Ebionites” found in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible.

Conversely, Tertullian, Hippolytus, and Epiphanius associate the name with a purported founder named Ebion, born in the village of Cochabe in Bashan. However, historical evidence validating the existence of this figure is scarce, leading to the likelihood that Ebion is a fictitious character crafted to elucidate the name “Ebionites.”

It is plausible that the sect might have embraced the name independently, asserting their commitment having sprung out of the early Jewish Christians in Jerusalem who embraced voluntary poverty and shared their possessions.

Alternatively, the name could have been externally imposed, possibly stemming from the recognized poverty of Jewish Christians in Judea. Contemporary scholars posit that the term initially referred to orthodox Jewish Christians in Palestine, upholding the Mosaic Law, that Catholic Orthodoxy gradually diverging from as it evolved into heresy.

The evolution of this divergence becomes particularly apparent in Justin’s “Dialogue with Trypho the Jew,” a significant work where he discerns two distinct sects among estranged Jewish Christians. On one hand, there exists a faction that diligently adheres to the Mosaic Law, retaining a strict observance of its precepts.

Simultaneously, the Nazarenes, within the same broader category, begin to deviate from the traditional views of Torah Judaism, marking a departure from the established norms. Despite this theological shift, Justin Martyr, a prominent Christian apologist, continues to maintain communion with the Ebionites.

“The gospel used by the Ebionites stated that Jesus had come to destroy sacrifices; unless sacrifices were terminated (in the temple at Jerusalem) men would not be saved.” – Robert M. Grant, A Historical Introduction to the New Testament

The Ebionites were acknowledged for using the Gospel of Matthew, and their distinct understanding of Christology is evident in their unique rendition of this gospel. Noted for their reliance on the Gospel of Matthew, the Ebionites presented a version that offered distinctive perspectives.

“They too accept the Matthew’s gospel, and like the followers of Cerinthus and Merinthus, they use it alone. They call it the Gospel of the Hebrews, for in truth Matthew alone in the New Testament expounded and declared the Gospel in Hebrew using Hebrew script.” Epiphanius, Panarion 30.3.7

According to Robert M. Grant in “A Historical Introduction to the New Testament,” the Ebionite gospel underscored Jesus’ mission to abolish sacrifices, emphasizing the cessation of sacrifices in the Jerusalem temple as a path to salvation.

Bart Ehrman’s research revealed intriguing differences, such as the Gospel of the Ebionites portraying John the Baptist as a strict vegetarian. Epiphanius, citing the Gospel of the Ebionites, described Jesus as a proselyte who later wrote against circumcision, the Sabbath, and the Law.

Scholars actively engage in debates regarding the potential relationship between the Ebionites and the Nazarenes, with varying viewpoints on whether they essentially constitute the same religious group. Traditionally associated with the early Jerusalem community, the Ebionites contrast with the Nazarenes, often viewed as a post-70 CE faction seeking refuge in Pella following the Jewish War.

A defining characteristic of the Ebionites is their rejection of Jesus’ pre-existence and divinity, a pivotal tenet that distinguishes them. Their unwavering adherence to Jewish customs and meticulous observance of the Law further set them apart from their early Christian counterparts.

The plausible historical connection between the Ebionites and the Jerusalem Synagogue is underscored by shared characteristics, including their emphasis on Law observance, aversion to Paul, and the orientation of prayer toward Jerusalem—a alignment with the beliefs and practices of the initial Jerusalem Christians.

Significantly, Origen identifies two primary factions within the Ebionites, one rejecting the virgin birth, while the Nazarenes embrace it. The latter group, aligned with the Gospel of the Hebrews, exhibits a textual affinity with the Gospel of Matthew.

According to The Daily Beast, the Talmudic authors refer to Jesus as “Yeshu ben Pantera,” translating to “Jesus son of Panther.” This name, “ben Pantera,” was commonly associated with Roman soldiers in rabbinic literature. Notably, references to the “son of Pandera” appear in the Tosefta, Qohelet Rabbah, and the Jerusalem Talmud, but not in the Babylonian Talmud.

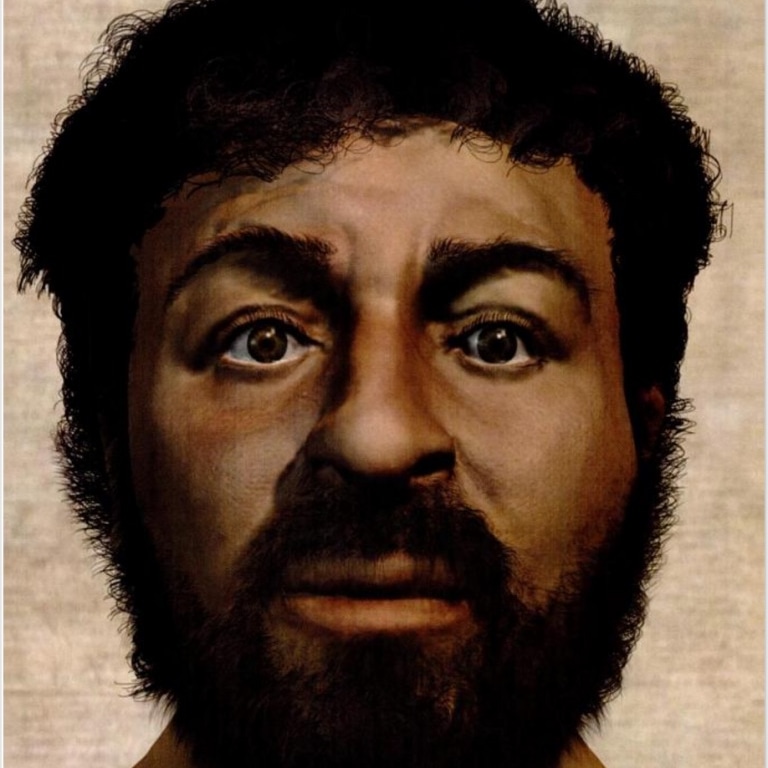

In the 2nd century, Greek philosopher Celsus asserted that Jesus’s father was a Roman soldier named Panthera. The 4th-century Christian apologist Epiphanius seemingly takes the designation seriously, suggesting that “Jesus son of Pantera” is a nickname for Jacob, the father of Joseph and husband of Mary. Was Jesus father a Jewish Solider who served in the Roman Army? This is a good question.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, presented by J.P. Arendzen, discusses the Ebionites, noting that those who accepted the virgin birth held more exalted views of Christ. This subgroup, in addition to observing the Sabbath, commemorated Sunday as a memorial of His Resurrection. Arendzen suggests that the milder Ebionites, who accepted the virginal birth, were likely fewer and less significant than their stricter counterparts, as the denial of the virgin birth was commonly attributed to the entire group. Epiphanius distinguishes between the more heretical faction, termed Ebionites, and the more Catholic-minded group, referred to as Nazarenes.

Jeffrey Butz posits a fascinating perspective on the relationship between the Ebionites and the Nazarenes in his work “The Secret Legacy of Jesus.” According to Butz, the Ebionites and the Nazarenes are essentially synonymous. He suggests that following the upheaval of the Jewish War, the Nazarenes sought refuge in Pella, forming a community in exile. It is at this juncture, according to Butz, that it becomes more fitting to designate them as the Ebionites. Notably, Butz contends that there was no distinct demarcation or abrupt shift in theology or Christology from Nazarene to Ebionite; the transition was gradual.

Despite later church fathers treating Nazarenes and Ebionites as distinct Jewish Christian groups, Butz argues that they were one and the same. To enhance clarity, he proposes referring to the pre-70 group in Jerusalem as Nazarenes and the post-70 group in Pella and other locations as Ebionites. This perspective challenges conventional notions, urging a reconsideration of the historical continuity between the Nazarenes and the Ebionites.

Irenaeus posited that the Ebionites’ doctrines bore semblance to those of Cerinthus and Carpocrates. Their rejection of the divinity and virgin birth of Christ, steadfast adherence to the Jewish Law, and the categorization of Paul as an apostate were central tenets. Exclusive acceptance of the Gospel according to Matthew was a defining feature. While Hippolytus and Tertullian echoed similar descriptions of their beliefs, the emphasis on Law observance was less pronounced compared to Irenaeus’ account.

Origen introduced a nuanced perspective, distinguishing between two classes of Ebionites. Some acknowledged the virgin birth of Christ, while others rejected it; however, both factions rejected His pre-existence and divinity, seeing him as only a man with an earthly father and mother. The adherents of the virgin birth held loftier views of Christ and observed both the Sabbath and Sunday as a commemoration of His resurrection.

Origen frequently noted the divergence within the Ebionite community regarding the birth of Christ, with some acknowledging the virgin birth but unanimously rejecting his pre-existence and essential divinity. This denial constituted the core heresy according to early Church Fathers like Irenaeus. How the early Church called their foundation heresy is amazing!

Geoffrey W. Bromiley, highlights that certain Ebionites rejected “the virgin birth” and “refused to acknowledge that he pre-existed, being God… they turned aside into the impiety of the former, especially when they, like them, endeavored to observe strictly the bodily worship of the law,” however the Nazerenes aligned, to some extent, with the more heterodox faction.

Epiphanius labeled the more heretical branch as Ebionites, while the more Catholic-minded group was called Nazarenes. Nevertheless, the reliability of Epiphanius’ information and its source remain uncertain, casting doubt on the assertion that the distinction between Nazarenes and Ebionites dates back to the earliest days of Jewish Christianity.

In “Jewish Ways of Following Jesus,” Edwin K. Broadhead highlights Theodoret’s classification of Ebionites into two groups based on their stance on the virgin birth. The Ebionites who reject the virgin birth are associated with the Gospel of the Hebrews, while those who accept it are linked to the Gospel of Matthew in contrast to the Gospel of the Ebionites.

The Ebionites were known to use there on Hebrew Gospel, and their distinctive understanding of Christology can be seen in their unique version of this gospel. Bart Ehrman’s research highlights intriguing differences, such as the Gospel of the Ebionites presenting John the Baptist as a strict vegetarian.

In his work on patristic evidence for Jewish-Christian sects, Albertus Frederik Johannes Klijn notes that Irenaeus mentioned the Ebionites using the Gospel of Matthew. Notably, Irenaeus, unlike Eusebius, did not explicitly connect his mention of Matthew with Origen’s discussions about the ‘Gospel of the Hebrews’.

Apart from the predominantly Judaistic Ebionites, a subsequent Gnostic branch of the sect surfaced closely associated with the Nazarenes. These Gnostics diverged notably from the main Gnostic schools by rejecting any differentiation between the Demiurge and the Supreme Good God.

Some scholars, emphasizing the significance of this distinction to Gnosticism, may dispute categorizing Ebionites as Gnostics. However, the overall essence of their teachings undeniably exhibits Gnostic traits. This is evident in the Pseudo-Clementine writings, where matter is viewed as eternal, forming part of their emanative cosmology.

In “Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew,” Bart D. Ehrman examines the Gospel of the Ebionites, highlighting its unique portrayal of John the Baptist adhering strictly to a vegetarian diet, similar to Jesus.

G.R.S. Mead, in “Gnostic John the Baptizer: Selections from the Mandæan John-Book,” adds depth by presenting an account where John, before Archelaus and the Law doctors, attributes his purity and sustenance to the guidance of the Spirit, emphasizing a diet of cane, roots, and tree-food, symbolizing a spiritual connection with nature.

Ehrman, in “Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament,” reinforces this insight, referencing Epiphanius’ citation describing John’s food as wild honey with a taste reminiscent of manna.

While the historical influence of the Ebionites diminished over time, their unique perspectives and practices offer valuable insights into early Jewish Christianity. The exploration of their beliefs, the historical foundations surrounding their origins, and their distinct Hebrew Gospel contribute to the diverse landscape of early Jewish Christianity.

The Ebionites, despite fading into obscurity, hold a very important place in the history and reseach of who the historical Jesus was. Recent research has shed light on their relationship with other Jewish Christian sects, and their impact on the development of Christian doctrine.

The Ebionites, despite their historical obscurity, offer a valuable window into the diversity of early Christianity. Their unwavering commitment to Jewish law and their unique Christological perspectives challenge us to re-examine the development of Christian dogma and the ongoing dialogue between Judaism and Christianity.

Scholars continue to study the Ebionites, exploring their historical context, theological beliefs, and influence on other Christian groups. Their commitment to Jewish law, their rejection of Pauline teachings, and their unique understanding of Jesus provide a counterpoint to the dominant narrative of Christian orthodoxy.

By studying the Ebionites, we gain a deeper appreciation for the richness and complexity of early Christian thought and the ongoing dialogue between Judaism and Christianity. Despite their decline, the Ebionites continue to fascinate scholars and offer valuable insights into the early history of Christianity.

Leave a comment